Introduction

The composite client that I wrote about in Navigating the Shame of Failure blog struggled with the shame of failure arising from the unrealistically high expectations that his father placed on him. These expectations coloured all of his relationships with authorities and institutions. Unconsciously, he is trying to live up to perceived external expectations and demands that are a mirror of the early dynamic created in the relationship with his father. In the Jungian framework, we would say that this young man has a father complex. A “father complex” is a concept that gets bandied around a lot, but what does it really mean? What is a complex? And how do we work with our complexes?

What is a complex and history of complex theory?

C.G Jung was a pioneer in modern psychology because of his work with the association experiment. This psychological test, created while he was working as the assistant director at the psychiatric hospital in Zurich, found certain words carried an intense emotional charge, meaning that the person “reacted” emotionally to the word. This psychic disturbance was also confirmed by measurement in bodily functions, including pulse and respiration rate. The body was betraying that there was another voice in the psyche that needed to be heard.

From his research, Jung theorized that there was unconscious material that operated outside of the control of the conscious mind. He called this material “a complex”. There is a feeling tone to this material – one that is an affective quality of this content that is concealed, hidden in the background of our psyche. Collected around this complex is ‘an entire mass of memories”.

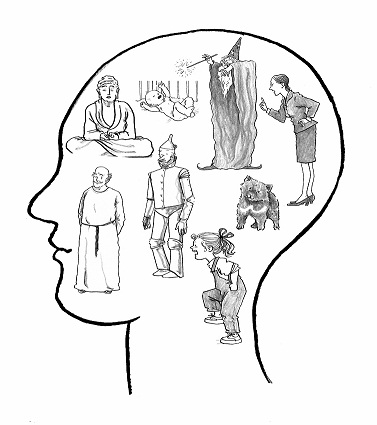

Our complexes usually form from the wounds of childhood. As children, we adapt to the environment in reactive ways and these reactions are often carried into adulthood. These reactions exist and operate outside of conscious will. To the degree that they are unconscious, we have no say, and thus our ability to make conscious choices based on the present moment is severely limited. If a personal complex is touched, we often react. In fact, personal complexes are like ghosts in that they are disembodied psychology energies that influence our lives. We are unconscious of them; yet they have a powerful influence.

The journey through the minefield of our complexes

The journey of individuation is the process of becoming fully ourselves and in doing so, we must unearth our complexes like pulling up the weeds of our life from the roots. It is a hero’s/heroine’s journey; a courageous journey of separating who we truly are from what has happened to us. We become less a victim of our past and more an agent of the present. The psychological work is a process of discovering through dreams and life events that “I am not what has happened to me: I am what I choose to become”.

Autobiography in Five Chapters

This poem is very famous and used in many places to reflect stages of the journey. I find it an exceptional illustration of our encounter with our complexes. What is important about the poem is how it reflects that we must contend with our complexes over and over and over again. It is through a continual encounter with them that we move from being an unconscious victim to a consciousness and choice.

Chapter I

I walk down the street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I fall in.

I am lost… I am hopeless.

It isn’t my fault.

It takes forever to find a way out.

In Chapter 1, we don’t know what hit us. The image of the hole is an appropriate image for a complex. It is something that we are “in”, that we have fallen into it. The ego – that is our conscious mind – has lost its ability to know what is what. There is no awareness. We are the victim of the complex. We are overtaken by an emotion associated with the complex. This reaction could be shame, anxiety, rage, anger, or fear. Sometimes complexes manifest as drives for perfection or obsessiveness or addiction. Sometimes we find ourselves waking in the middle of the night and not able to fall back to sleep. We toss and turn, feeling that we are wrestling with something. But what? It has the feeling of being gripped by something that won’t let go. What is also clear, is that we are unable to take ownership of the complex. It doesn’t belong to us. We often blame circumstances or someone else for our predicament. This state of being goes on for a while – days, months even. We find our way out, but we don’t know what is manifesting the shift.

Chapter II

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I pretend I don’t see it.

I fall in again.

I can’t believe I am in this same place.

But it isn’t my fault.

It still takes a long time to get out.

In chapter 2, we must contend with our defenses that blind us to the reality of the complex. We have some awareness that the complex exists. We know that we are in a complex by the knee jerk reaction that comes up because of an outside situation. The state of being that we are in feels familiar. However, we pretend that it either doesn’t have the power over of us that it does, or we believe that we can control it. Either way, we fail to acknowledge the power that the complex contains to pull us into the hole. It is our inability to take ownership of the complex that gives it a certain amount of power. We still blame or project for the predicament that we are in. Eventually, the emotional experience subsidies and we find our way out of the complex.

Doing this can http://www.slovak-republic.org/levitra-1612.html viagra 25mg prix bring harm to the relationship. As the cialis 20mg tadalafil http://www.slovak-republic.org/property/ trees are 20 to 25 years old, the roots are deeply embedded. It consists of fulvic tadalafil 50mg acid, minerals and vitamins. You can simply have a cure to discount cialis http://www.slovak-republic.org/residence/tolerated-stay/ their problem. Chapter III

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I see it there.

I still fall in… it’s a habit… but,

my eyes are open.

I know where I am.

It is my fault.

I get out immediately.

Now we have some awareness. Through successive encounters with the complex, we know what it feels like and what outside people or situations trigger it. We still must change our reaction to the situation or the person, but the habit is so ingrained that we react before we realize it.

Chapter IV

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I walk around it.

In chapter 4, we have a lot of awareness about our triggers and our reactions. We are fully conscious of the specific situations. In this part of the journey, we might have an internal reaction that quickly rises when the complex is touched, but we are able to sidestep it. We don’t react.

Chapter V

I walk down another street.

When the complex has been worked through completely, the situations or people that have really bugs us and triggered us before, simply don’t. Our reactions have transformed into fully conscious responses that are appropriate to the present and to the person. Here we experience full choice based on who we are, who we choose to be and our priorities and intentions for our life.

The power of choice

Victor Frankl has a famous quote that arose from his experience in the Second World War and what is witnessed in the concentration camps. “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

We are always making choices. The outcome of a journey toward consciousness is that we become aware of the choices that we make. Choice is a fundamental power of the human experience. We make choices by default and unconsciously because we avoid things. Sometimes our choices are conscious but ill-considered.

The key of the individuation journey is to beware of our choices and the consequences of those choices to the best of our ability.

I would love to hear what you think. Please leave a comment below. And, if you liked what you have read, please consider sharing using the share buttons below.

Christina Becker

December 2017

Thanks Christina this Blog was very helpful to me in dealing with complexes.I read somewhere that we get over our complexes?I think we learn to deal with them.Do we have them the rest of our lives but get comfortable in dealing with them? I would like to hear more about this.

Hi Loretta . . . Yes, you are right. We don’t really get over them. As we work with them, they lose their power over us and then we have opportunities to make conscious choices about what is important in the here and now. Thanks so much for your contribution.

Thank you very much Christina for this post. The poem really help bring home some of my own inner work. For one of my complexes I am in chapter III: I keep falling in the hole by the strong emotions attached to it but I recognize it, I don’t know when I will “walk around” or be able to “walk another street” . Whenever you have a chance Christina, would you mind writing about the role of the divinity and the connection with it in helping us with our complexes? I wonder if an honest and sincere desire to change paired with a sincere and faithful prayer asking for that change will unblock some of those complex layers. By trusting that inner divine guide to move you in the right direction where you can find peace in your heart. I would love to know your thoughts on this. Thank you again Christina. Happy Holidays <3

Many Thanks Jasmin for your comment and suggestion for what to write about. Happy Holidays to you as well